BENGALURU: In the ever-evolving digital landscape, artificial intelligence (AI) has permeated various facets of human interaction, offering an impressive array of services through AI chatbots.

These virtual assistants, designed to engage users through natural language processing and machine learning, have rapidly gained popularity. However, beneath the surface of convenience and user engagement lies a disconcerting reality: the extent to which these chatbots collect and manage user data.

Recent findings from a study conducted by cybersecurity firm Surfshark shed light on a pressing issue – the pervasive data collection practices adopted by these AI platforms, some of which extend to sharing users’ information with third parties.

The research by Surfshark highlights a rather alarming trend among the leading AI chatbots available on the Apple App Store. While these applications promise enhanced interaction and personalised assistance, they simultaneously initiate a complex relationship with user privacy.

According to the study, all ten of the most popular AI chatbots not only engage in gathering various types of user data but to exacerbate concerns regarding privacy, 30 per cent of them reportedly share this data with external parties. Such practices often cater to the interests of targeted advertising and data measurement enterprises, as well as third-party brokers.

Raises eyebrows

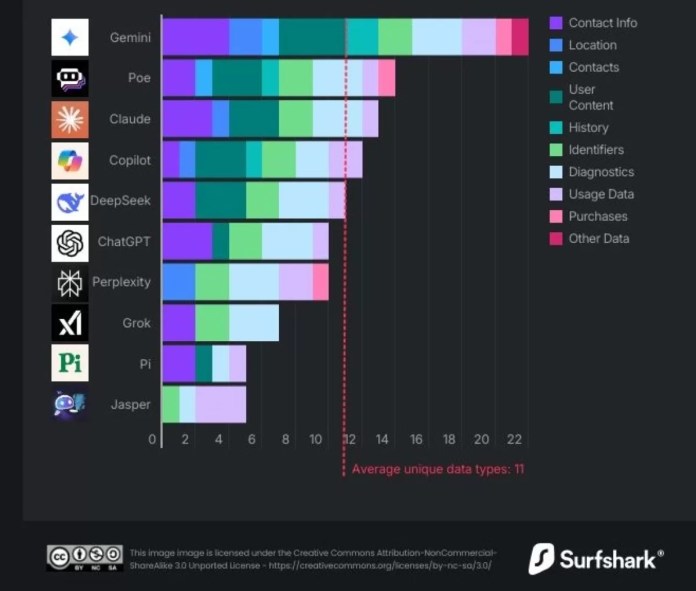

A closer examination of the data collection practices reveals that Apple’s App Store privacy guidelines outline 35 distinct types of data that applications may potentially accumulate. On average, these chatbots assimilate around 11 different types of user data, which could range from personal identifiers to usage patterns.

Notably, Google’s Gemini chatbot stands out in the realm of data collection, with an extensive repertoire of 22 types of assimilated data. This includes not only the user’s precise location but also a plethora of other sensitive information, such as contact details—name, email address, and phone number—as well as user-generated content, browsing history, and stored contacts.

Such exhaustive data accumulation brings forth substantial implications surrounding user autonomy and control over personal information.

Critics of these extensive data collection initiatives have voiced concerns that such practices can be perceived as excessive and intrusive. The recent discourse surrounding digital privacy underscores a growing unease among users about the extent of surveillance they unwittingly invite into their lives.

As Surfshark researchers aptly noted, the accumulation and potential commodification of their personal data can instigate apprehension among individuals who prioritise safeguarding their digital identities. This discourse raises compelling ethical questions regarding the balance between providing personalised service and the right of users to retain control over their personal information.

In contrast, OpenAI’s ChatGPT has purportedly adopted a less invasive approach to data collection, reportedly gathering only ten types of data. This includes crucial identifiers, usage data, and user content, yet this chatbot has elected not to engage in third-party advertising, which adds a layer of assurance regarding user privacy.

Monetisation of user data

Nevertheless, it must be noted that ChatGPT does maintain a chat history, although users are afforded the flexibility to enable temporary chats that auto-delete after 30 days or to request the removal of their personal data from training datasets. Such options contribute positively to the discourse on user agency, but they also evoke further scrutiny regarding what constitutes an adequate privacy policy.

The analysis of other chatbots presents a similarly troubling picture. The Chinese chatbot DeepSeek is characteristic of an operational model that collects 11 unique types of user data and maintains chat history without explicit transparency on data usage policies.

The assertion that user information may be retained “for as long as necessary” and stored on servers located in the People’s Republic of China raises critical concerns about data sovereignty and international privacy standards. This underscores the imperative for individuals to contemplate the implications of utilizing applications developed in jurisdictions with distinct regulatory frameworks.

Chatbots such as Copilot, Poe, and Jasper AI also reveal a concerning trend towards the accumulation of data that holds potential for tracking users.

Jasper, for instance, collects product interaction data and advertising data, which can be utilised for targeted advertisement or sold to data brokers.

The monetisation of user data significantly complicates the nexus of personal privacy and corporate interests, necessitating a comprehensive approach to user education and regulation in the burgeoning field of AI.